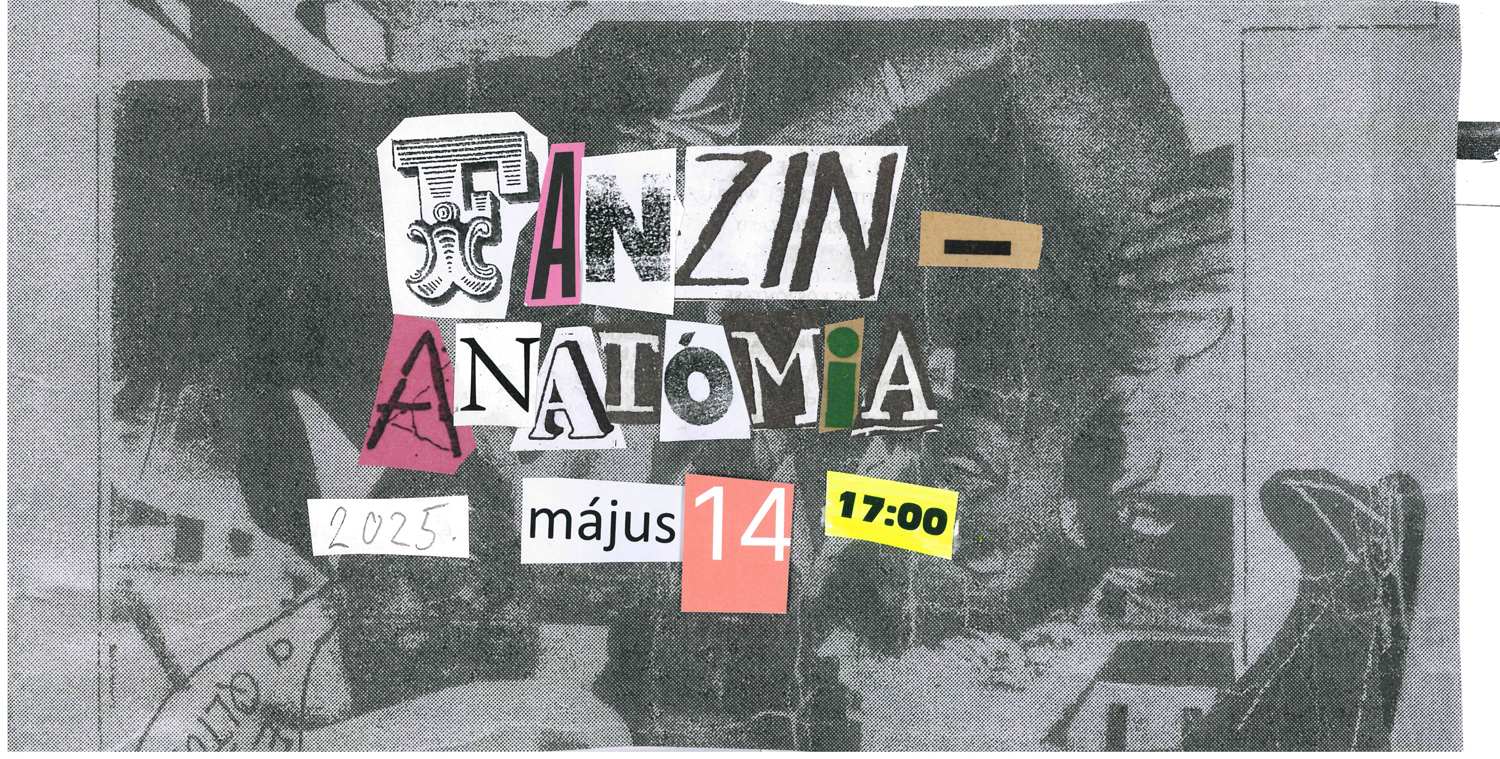

Fanzine Anatomy

Alternative Hungarian Publications on Music and Politics from the Artpool Collection

14 May – 19 September 2025

Artpool Art Research Center

1135 Budapest, Szabolcs u. 33. Bldg. D

Opening by: Bea Istvánkó (ISBN+), 14 May 2025 at 5 pm - facebook event

➤ opening speech (in Hungarian)

➤ photos from the exhibition opening

Curators: Éva Bárdits, Viktor Kotun, Zsófia Kókai, Gabriella Schuller

◼︎

Guided tours:

11 June 2025 (guided tour by the curators) - facebook event

2 July 2025 (guided tour by the curators) - facebook event

◼︎

Zine-making workshop:

15 July 2025., 3–6 pm - facebook event

(led by Julcsi Domján and Anika Kisvarga, founders of Zabella Zine)

◼︎

FINISSAGE: CONCERT AND VIDEO INTERVIEW MARATHON

19 September 2025, 12:00 – 19:00 - facebook event

On the final day of the exhibition, we will screen all of the video interviews created in connection with Fanzine Anatomy in their entirety.

Interviewees:

• Judit Acsády, sociologist, activist, editor of the feminist magazine Nőszemély, member of the Feminist Network

• Zoltán Legény (“Dr. Slayer”), creator of the Total Addiction fanzine, influential figure in the hardcore punk scene, member of Human Error

• Mihály Rácz, pioneer of Hungarian fanzine culture, creator of the Mély Vágás and Második Látás fanzines

• Tamás Rupaszov, founder of the band Trottel and Trottel Records, key figure and organizer in underground music culture since the 1980s

After the screening, Viki Taskovics, an active participant in the contemporary punk scene in Szeged and Budapest (currently in the band Energia80) and a researcher of subculture, will perform.

Program:

➤ Video interviews:

12:00-13.00: with Judit Acsády

13:30-14.30: with Zoltán Legény

15:00-16.00: with Mihály Rácz

16:15-18.00: with Tamás Rupaszov

➤ Concert:

18:00-18.30: Viki Taskovics plays guitar

The collection display can be viewed (free of charge) by appointment on weekdays until 19 September, 2025:

artpool@szepmuveszeti.hu

Introduction

The original English word fanzine is a portmanteau of “fan(atic)” and “magazine” and thus it broadly means a ‘fan magazine’. While, from the 1940s onwards, the term (1) originally referred to the publications circulated among American science fiction fans, it is often associated in the popular imagination with the punk movements of the West. The ideal type of the fanzine rose to prominence and became a powerful medium of community organisation in the 1980s: an autonomous, self-published, low-circulation and cheaply produced collage-style photocopied magazine created for and about a specific community (and subjects they were preoccupied with).

Samizdat, i.e. self-publishing as a form of resistance to official censorship, was also well known in Hungary(2); Artpool’s “samizdat” journal Aktuális Levél / Artpool Letter was the first domestic publication to address the phenomenon of the fanzine.(3) However, the themes, subcultural target audience and social context of fanzines differed significantly from those of samizdat publications and their makers often drew inspiration from Western models.

From the second half of the 1980s, with photocopying becoming accessible in Hungary, fanzines began to proliferate, although the pioneers of the genre frequently faced harassment by the authorities: for example, the police pressured Mihály Rácz – creator of Mély Vágás [Deep Cut] (later Második Látás [Second Sight]) – to cease publication of his magazine in 1987.(4)

The restrictions imposed on community organisation and political expression were gradually removed with the democratic change, fostering the flourishing of fanzine culture. “Life was happening – we had intellectual nourishment, including fanzines. There was no internet yet; it’s hard to imagine today,”(5) says András Madár, speaking of the fanzine culture of the 1990s and the prominent role these publications played in information sharing before the advent of the web. Madár worked at the Wave and Mover record shops, which were key venues for fanzine distribution alongside events, concerts and postal networks. Zoltán Legény, creator of the hardcore punk fanzine Total Addiction (which was instrumental in introducing the crust punk genre to Hungary), recalls the second half of the 1990s thus: “I devoured fanzines in both Hungarian and English, so I was flooded with information, at least as much as it was possible under the circumstances back then, in a world without the Internet.”(6)

In the 2000s, discourse related to marginal subcultures increasingly shifted into the online realm, particularly to dedicated forums, blogs, and webzines, many of which were launched by former (offline) fanzine creators. This transformed the role of fanzines and marked the end of an era. The tradition of alternative self-publishing and the DIY ethos primarily continued on the art scene, where aesthetic quality took precedence (over political, communal and social dimensions).(7) The Ukmukfukk Zinefeszt, held annually since 2016, provides a representative overview of the contemporary scene and “primarily focuses on visual and illustrative zines”.(8)

The fanzines displayed at our exhibition were published (or launched) in the 1980s and 1990s and fall into two main categories: publications linked to punk and other alternative subcultures and/or focussing on music; and politically and socially engaged zines, primarily anarchist in tone, as well as a specific feminist publication. These are often interlinked in many ways: an anarchist zine might be based on punk lyrics, while music fanzines contain numerous reflections on social issues.

As a (counter)cultural phenomenon, the fanzine is deeply entwined with the notions of independence, free self-expression, personal freedom and social liberation. Basic characteristic features of the genre are stylistic and thematic radicalism, a norm-defying stance as well as the use of subjects, ideas, modes of expression and visual forms of expression that are rejected by mainstream society and marginalised in public discourse. Many fanzines contain the critique of specific social issues or events and even the parody of the mainstream press products.

Alternative scenes and subcultures often create their own behavioural codes and canons, which also appear in fanzines. These norms and symbols strengthen group identity and cohesion, while creating a sense of exclusivity but they also impose (self)-restriction that significantly shapes the distinctive linguistic and visual styles of the publications. At the same time, fanzines not only resemble one another but also draw on genres familiar from mainstream media: no artist’s imagination can entirely escape prevailing social conventions.

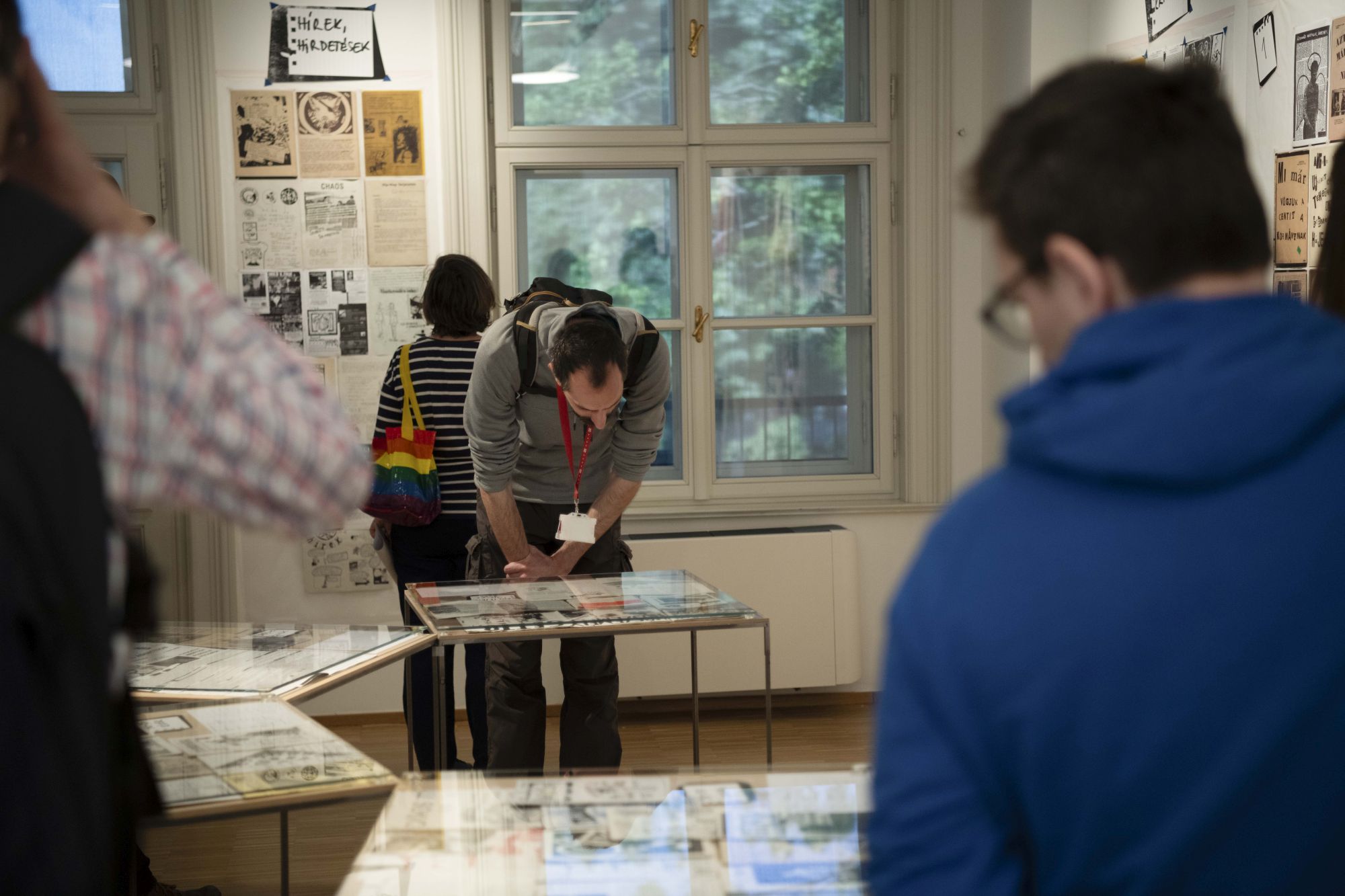

Our exhibition models the typical structure of a fanzine: beneath seemingly chaotic editorial principles, a recurring structure emerges that borrows from the standardised formats of the mass media (not coincidentally, many “fanzine people” later became professional journalists). We have arranged (sometimes enlarged) reproductions of fanzine pages into successive thematic sections, such as interviews, opinion pieces, concert reviews, music criticism and fanzine critiques: we have thus created a fictional fanzine anthology that reveals the basic underlying structure, or anatomy, of these publications.

To accompany the exhibition, we conducted interviews with Judit Acsády (Nőszemély), Zoltán Legény (Total Addiction), and Mihály Rácz (Második Látás).

.

The display of the collecion is dedicated to the memory of László Klein (1974–2021).

●●●

Notes ⇧

1 “I try to get in touch with bands, labels, etc., that I either really like or consider positive and useful in some way; in this respect, Látás [Sight] is even more of a FANzine in the original sense of the word.” Mihály Rácz. Második Látás [Second Sight], 1994/11, 2.

2 On the history of samizdat in Hungary, see Miklós Haraszti: A civil kurázsitól a civil társadalomig [From Civil Courage to Civil Society]. In: Szamizdat. Alternatív kultúrák Kelet- és Közép-Európában 1956–1989 [Samizdat. Alternative Cultures in Eastern and Central Europe 1956–1989]. Stencil Kiadó – Európai Kulturális Alapítvány, Budapest, 2004. 74–89.

3 Tamás Szőnyei: Szükség volt egy alternatív szócsőre... Beszélgetés Mark Perryvel [There Was a Need for an Alternative Mouthpiece… Interview with Mark Perry]. Aktuális Levél / Artpool Letter], 1984/9, 40–47.

4 “The punkzine MÉLY VÁGÁS [Deep Cut] was launched in January 1987. It set itself the objective to be published regularly and I was the editor myself. It was shut down by the police after three issues (January, April and July 1987).” Mihály Rácz: Feljegyzések a magyar gerillasajtóról [Notes on the Hungarian Guerrilla Press]. Mozgó Világ, 1993/12, 141.

5 „Mindig óriási bulik voltak, kikapcsolódott mindenki”. Interjú Madár Andrással. [“There were always massive parties, everyone was uwinding.” Interview with András Madár]. In: Nem az a punk, aki… Vol. 2 [Not All Punks Are… Vol. 2]. Magyar punk [Hungarian Punk] 90–04. Eds. Mihály Rácz and Tamás Rupaszov. Trottel Books, Budapest, 2024, 418.

6 „A tapasztalatokból kezdett összeállni a kép.” Interjú Legény Zoltánnal [“The experiences were starting to come together into a clear picture.” Interview with Zoltán Legény]. Ibid., 503.

7 “The primitive, unpolished, raw, vulgar, sometimes funny, sometimes crude, sometimes un-PC phrasing, which were hallmarks of punk, as well as the low technical quality of execution were replaced by a kind of new aestheticism, which was not independent of the visual turn in the socio-technical environment and fitted in with the all-pervasive general process of aestheticisation.” Szilvi Német: Elvesztette szubkulturális jellegét? A fanzine mint alternatív médiatermék művészeti piacosítása [Has It Lost Its Subcultural Character? The Fanzine as an Artistic Commodification of an Alternative Media Product]. Szépirodalmi Figyelő [Literary Observer], 2020/6, 48.

8 Petra Hoffman: Ukmukfukk Zinefeszt az Ankert-ben. [Ukmukfukk Zinefest at Ankert], Stilblog, 27 April 2018. ⇧

Publications presented at the exhibition ⇧

A Búvárok Reménykednek

AAAARGH!

Aktuális Levél

Anarchista Újság

Anarchoid

Anarchokommunista Akció

ARTalom

B.I. Kisasszony

Black Hód

Buka

Chaos' 77

Dall-ass

Decibel

Egyenesen Át!

Életjel

Feszültség

Genyó Szívó Disztroly

Gép-frújít

Getto

Hatalomtalanítás

Isten Malaca

Kero-ZINE

Lyukság

Marsbéli Krónika

Második Látás

Maszek Ideggyógyász

Mocskos szoba

Mozgalom

Napocska

No future!

Nonkonformist

Not Censored

Nouva

Nőszemély

Olvasnivaló

Ordító Egér

Raptér

Skandal

Straight Edge

Survival

Szabad Alternatíva

szART

Szeméttelep

Szubkultúra

Szűkbőrű

TACS

Telihold

The G-zone

Total Addiction

Tűzvonal

Világ-kép

Vírus

Warning Again

⇧

Literature available for research at Artpool ⇧

Nem az a punk, aki… Vol. 2. Magyar punk 90–04. Szerk. Rácz Mihály–Rupaszov Tamás. Trottel Books, Budapest, 2024.

Nem az a punk, aki… Vol. 1. Magyar punk 80–89. Szerk. Máté Zsuzsa–Rácz Mihály–Rupaszov Tamás. Trottel Books, Budapest, 2023.

Dűlő 2022031–2022032 – ZINE. Mikrokiadványok, selfpublishing, alternatív nyomatok. Szerk. Kazsimér Soma. Szépmesterségek Alapítvány, Miskolc, 2022.

Simon Ferenc: A hardcore utolsó nyomtatott mentsvára – Interjú a Reaction fanzine főszerkesztőjével. Nuskull.hu, 2021. december 9.

Farkas László: Így született a H.I.T. magazin. Egy kis magyar dark underground sajtó- és internettörténelem. Hun Industrial Tech, 2021. november 23.

Szabó Eszter Ágnes–Rácz Mihály–Klein László: Második Látás. Kulturális búvópatakok a 90-es években. Új Művészet, 2021/3. 26–31.

Német Szilvi: Elvesztette szubkulturális jellegét? A fanzine mint alternatív médiatermék művészeti piacosítása. Szépirodalmi Figyelő, 2020/6. 37–51.

Bihari Balázs: „Ez a vállalkozás nagyon punkosra sikerült”: a magyar fanzinek első hulláma. Szépirodalmi Figyelő, 2017/4. 55–69.

Rácz Rebeka: A zine-kultúra és a nyomtatás vizsgálata a digitális korban az Innen kiadón keresztül. BA szakdolgozat. Moholy-Nagy Művészeti Egyetem, Budapest, 2017.

Zahorján Ivett: Fénymásolt (anti)divat: a zine kultúra trendformáló hatásáról. Szépirodalmi Figyelő, 2016/6. 50–56.

Vásárhelyi Ágnes: Do I(nterne)t Yourself: A magyar hardcore punk és a virtuális tér. Replika, 2015/1–2. 79–98.

Reaction, 2015/6. Szerk. Sabján Bence.

Mucsi Emese: Have fanzine! Artmagazin, 2013/7. 24–29.

The Fanzine Show B&W. Budapest Edition 2010. Szerk. Kotun Viktor. Plágium2000, Budapest, 2013.

Golyhó Mytyx [Klein László]. Fanzine Show. Plágium2000, Budapest, 2011.

Teal Triggs: Fanzines. Thames & Hudson, London, 2010.

Klein László: Fanzinkiállítás és privát sajtótörténet. Irodalmi Jelen, 2009. július 19.

Il Vascello Delle Muse (Fanzine letteraria di cultura e libero pensiero). Szerk. Fabrizio Legger. 2009/2.

Karóczkai Zsolt: A fanzin megjelenése és szerepe a vizuális kultúra történetében, valamint felhasználásának lehetőségei a szaktárgyi oktatásban. Szakdolgozat. Szegedi Tudományegyetem Juhász Gyula Pedagógusképző Kar, 2007.

Klein László: Total Addiction 12. Punkportal.hu, 2006.

Rakk László: Szamizdat évtizede: a 80-as évek második nyilvánossága. Szakdolgozat. Szegedi Tudományegyetem, 2006.

Mód László: „Szentes Underground”. Egy kisváros ifjúsági szubkultúrái az 1990-es években. Múzeumi Hírlevél, 12. évf. 2004. 364.

Őz Zsolt: Zugló, géniusz, punk, menza. Riport Pozsonyi Ádámról. Népszabadság, 2003. június 14. 12.

Molnár Attila: A fanzine forma Magyarországon. Szakdolgozat. Eötvös Loránd Tudományegyetem, Budapest, 2001.

Seres László: Fogyassz és halj meg! Radikális fanzinek. Magyar Narancs, 1996. december 12. 26.

Rácz Mihály: Feljegyzések a magyar gerillasajtóról. Mozgó Világ, 1993/12. 141–146.

Sükösd Miklós: Az alternatív nyilvánosság, alternatív média Magyarországon I. rész: Helyzeti alternatívok. Mozgó Világ, 1993/11. 79–90.

Fanzinerie. Szerk. Piermario Ciani. Arcinova, Pordenone, 1992.

Fanzine as an ...Object. De Media, Eeklo, 1990.

Szőnyei Tamás: Szükség volt egy alternatív szócsőre… Beszélgetés Mark Perryvel. Aktuális Levél 1984/9. 40–47.

Alice Klein–Suzanne Little: Fanzines Talk Street. Now Communications Inc., Toronto, 1983. ⇧

Podcast, discussion, video interview ⇧

Agyampodcast 25. adás

Vendég: Dr. Slayer, 2025. január 13.

Wanted Podcast #40. Fanzine-kultúra Magyarországon – Rácz Mihály kalauzolásában, 2021. április 19.

Barangó a rendszerváltás körüli fanzine-okról és undergroundról,

2019. június 21.

Klein László, „Pöpe” és Vargyai Viktor: Walk together, rock together. Civil Rádió, Budapest, 2013. február 8.

(Meghallgatható az Artpoolban) ⇧

Digital fanzine archives ⇧

FCSMK (Fekete Csillag Műhely, Eger) E-polc

Magyar underground zenei fanzinok (Klein László gyűjtőmunkája) ⇧

Related exhibitions ⇧

Fanzine-ok és rendszerváltás. Lakáskiállítás és beszélgetések. Dobó Gábor lakása, Budapest, 2025. február 13–23.

„Ha az elmélet nem elég” – válogatás a Labor fanzine-gyűjteményéből. ISBN, Budapest, 2019. május 20. – június 25.

Miújság? Fiók – Ukmukfukk Zinefeszt, Budapest, 2017. április 26–27.

Az Ordító Egér. Történeti fanzine leltár. Higgs Mező, Budapest, 2014. április 12–24.

Fanzine Show. Egyszerű többség. Műcsarnok, Budapest,

2011. március 26. – április 23.

Könyvtér. Labor Galéria, Budapest, 2010. február 23.

Fanzinekiállítás. Gellner-terem, CEU, Budapest, 2009. június 26–27. ⇧